How can local gov’t support community led action?

March 2024: A series of four posts relating to my work creating a process, guidelines and resources for the Far North District Council’s new placemaking team.

Post 1: Overview

It’s a rare pleasure to finish work for a client knowing that it will be ‘field tested’ straightaway.

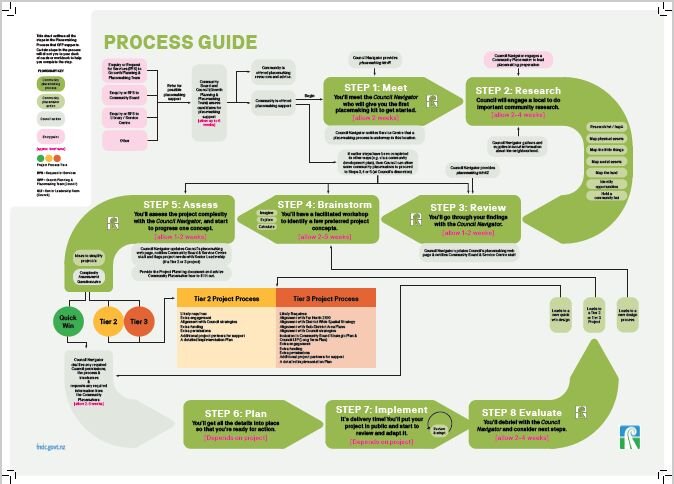

I finished developing a Placemaking Process Guide and Resources for Far North District Council last month, and this work will be put to the test starting soon in Kororāreka Russell – with a chance for further revisions following feedback from its first outing.

It’s great to be able to work with a client in this way, where a quick and meaningful feedback loop is part of the process.

Problems we have tried to address that we are putting to the test include:

· Do these resources make local government transparent and navigable for communities wanting to lead or instigate local placemaking and developments?

· Do this process and resources help build community capability and address inequity across the District?

· Have we succeeded in getting buy-in from Community Boards and multiple teams across Council to support the placemaking process?

· Does this process help us figure out how to deploy very limited Council placemaking resources (staff and budget)?

· Will this work equip the Placemaking team and local communities to feed more knowledgeably and confidently into higher-level growth and spatial planning processes underway in the District?

Post 2: Balancing Council’s enabling and regulatory roles

For a range of reasons – including better community development outcomes, cost savings to Council and limited Council resources – local governments often want communities to initiate and lead their own placemaking and community development projects.

At core, however, Councils are Territorial Authorities typically divided into units by function to control environmental safety and health, the effects of land use, noise, and so on. This enforcement role always sits in tension with that equally important community empowering role.

I think it’s an inevitable problem that Councils face.

One way to help reconcile this tension is by making Council transparent, understandable and navigable for communities.

To encourage and improve community-led placemaking in the Far North, I have created a step-by-step Process Guide.

It contains additional resources like a Getting to Know FNDC deck of cards with clear and simple explanations of different teams and functions in Council, and key terms that communities might encounter. These will be updated by the Placemaking team twice yearly to keep them current.

Alongside this, there will be a Council Navigator role to guide communities through the process and any required permits or approvals (and to be internal advocates for the community in seeking these approvals).

Through these mechanisms, we hope to make community-led development more inviting and easy, without sacrificing the rigour of Council’s regulatory role.

Post 3: On the importance of engagement and participatory design

A new Council Placemaking team is established to encourage more Community-led infrastructure and developments. But they can’t know in advance (or restrict) what ideas their communities will come up with.

The community might want to install something in a reserve or cemetery; narrow a traffic lane to widen a footpath; overhaul a public toilet block; extend outdoor dining hours; repair a seawall… This could require approvals from Parks, Transport, Asset Management, Facility Management, Policy, Climate Resilience and more.

If they’re not all on board with the kaupapa of the Placemaking work, you’ll be working at cross purposes.

To create the placemaking process and resources for Far North District Council, I met with more than 40 people at Council: community board coordinators and elected members, and team leaders and staff from twelve different teams.

All had valid concerns. Most had hopes for what this work could help solve. Council’s Placemaking Planner, Anna, sat in on every session.

Together, we learned all about the processes and aspirations for nearly half of Council.

By the end, we had a Parks & Reserves Planner offering to do opportunities analyses for communities based upon their neighbourhood’s Reserve Management Plans; a Transport Planner offering to produce neighbourhood maps indicating the One Network Framework classification of each road; a Funding Advisor offering to have a meeting with communities as a step in the placemaking process; and so on.

These other teams are offering their own resources to help the placemaking process because they understand it, support its purpose and see that their involvement will improve the outcomes for their teams, too.

Spending that internal engagement time should entail much better alignment across Council with the aspirations of the Placemaking programme.

And Anna is now well positioned to be that Council Navigator for communities, to understand Council’s processes and concerns and guide communities and their projects through them.

(The process felt so beneficial that the Climate Action & Resilience Manager has now asked me to follow a similar process to develop an Adaptive Pathway Planning process for her team – yay!)

We might have reached a similar end point and comparable deliverables without so much engagement, but with far lower levels of understanding and support throughout the Council organisation.

Post 4: On equity

It’s a tricky catch that neighbourhoods that already have the most wealth, education and privilege tend to be better at attracting funding and advocating for support to lead their own placemaking or community development projects.

In creating a placemaking process and resources for a diverse District like the Far North, I addressed this equity issue in a few ways.

Once a community is confirmed to receive support from the placemaking team, Council will engage – in a paid capacity – a community member or group to lead an asset mapping process in that neighbourhood.

This community representative (or group) will be paid a fixed fee to spend a few weeks

· researching and conversing with local iwi and hapū;

· mapping the physical assets of the neighbourhood and users’ sentiments;

· mapping the community groups, sports clubs and other social assets and their aspirations and resources;

· mapping the land ownership, natural hazard risks, vacant and neglected places;

· meeting with their Council Navigator to learn about the parks, zoning and Council facilities; and

· hosting a community hui to discuss the situation and opportunities.

This foundation encourages a broad view of the whole neighbourhood, establishes a strong initial relationship between Council and community and creates a community resource and knowledgeable leader that sets the place up well for ongoing community-led work.

We don’t want it to be a prerequisite that communities already have strong and active community groups. This process might help new groups to form where they don’t already exist.

It’s a tiered system, so communities new to this work are encouraged and supported to start with a small ‘quick win’ project with easy approvals – and build up to larger-scale work that might require resource consent, long-term plan submissions or significant stakeholder engagement.

This tiered system also makes it easy for Council to scale their approvals processes according to the significance (scale, duration, environmental impacts, etc.) of the project.

We hope that these steps will make it easier – or possible – for communities with no previous placemaking experience to get started, and for Council to direct its placemaking resources towards those who need them most.