Prototyping the Future

June 2024: PLACEMAKING FOR CIVIC IMAGINATION PART II. Placemaking as urban prototyping.

Gap Filler’s Dance-O-Mat, now in its sixth location.

Everyone I talk to has been feeling the pressure of the rising cost of living and the impact of extreme weather events in Aotearoa New Zealand. It’s difficult not to feel a sense of paralysis or resignation when faced with the scale and complexity of climate change, biodiversity loss, our ageing population and a wide range of other fiendish issues.

My local Council has been engaging people on managed retreat from coastal communities, and how to halve our city’s carbon emissions by 2030 (in six years!). There’s no sense of whether and how we might achieve either of these incredibly complex feats, and we know we need to do way, way more than this in order to build resilience in a rapidly changing climate.

Leading Gap Filler the past few years, I worked to reorient how we think about our placemaking work in light of some of these challenges facing communities, cities and humanity as a whole. The methodologies and principles of creative participatory projects that we developed served wonders for during the long recovery from devastating earthquakes.

I think these methodologies are equally applicable to preparing ourselves and taking community action as the impacts of climate change accelerate. We know that these methods can grow engagement and participation, lead to better decision making and empower communities to lead work themselves. The benefit I want to focus on here, however, is the work these projects do to open up the sense that change is possible. Participatory placemaking grows civic imagination.

Since a few of us humbly started doing some small quake recovery projects under the name Gap Filler more than 13 years ago, the organisation has realised more than 200 temporary installations and interventions in Christchurch – from murals to popup dance floors to the design, construction and operation of a fully consented temporary building – and led or supported more than 900 events.

The Placemaking at One Central programme ran for more than six years, at one stage covering as much as 15,000m2 of sites awaiting future residential development.

I got to manage a six-year-long placemaking programme from engagement to strategy to implementation working in partnership with one of the country’s largest residential developers, Fletcher Living. I had the chance to be part of civic space design teams and master planning processes around Aotearoa New Zealand, working alongside landscape architects, architects and planners. I’ve been invited to run workshops, give talks, act as a mentor and occasionally deliver projects in nine other countries. I’ve been lucky to have had lots of opportunities in a wide variety of circumstances to explore and consider how this sort of placemaking work can lead to longer-term change.

One key observation from this work is that we increasingly come up against the limits of people’s imaginations when it comes to civic engagement and co-creation. In a town where I’ve recently been working, something as straightforward as people living in apartments upstairs from some of the main street shops felt too radical for most people to imagine. (With no garage? Where would people park? What about the noise? Why would anyone ever do that?)

Of the 300 or so unsolicited emails Gap Filler received from people over the years with ideas for what our next Gap Filler project should be, 99% of them included some photos, a video or an article about something that had already been done somewhere else. Only a handful were truly original ideas, and most of those were in the first months after the earthquakes. People can (sometimes) imagine a project they’ve seen in Melbourne being successful in Christchurch; far fewer can imagine something new into existence. Our imaginations need help. We need to value and nurture and cultivate this crucial faculty.

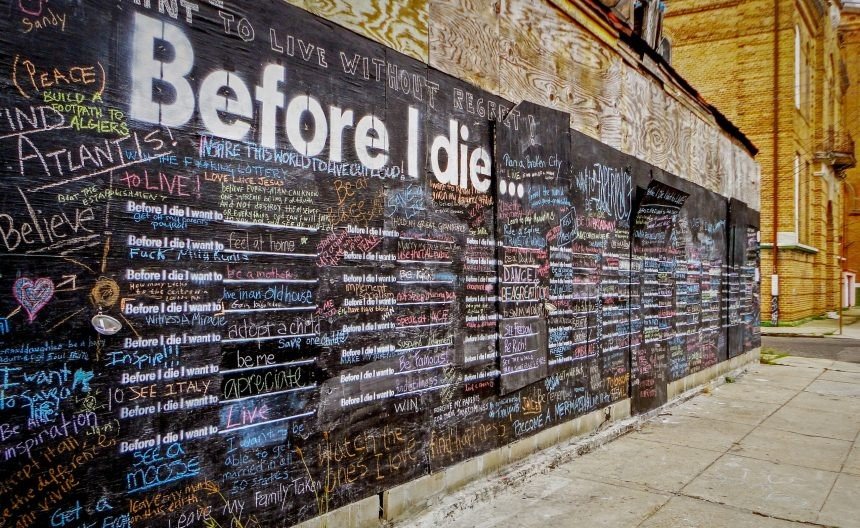

One of artist Candy Chang's infamous 'Before I die...' interactive artworks in post-disaster New Orleans. Approximately everyone I talked to in 2011 thought we should make one in Christchurch. (Photo by Candy Chang)

The scale of Gap Filler’s work is comparatively small. But I know some of our work has impacts that last long after the project’s completion and have the potential to shape people’s expectations of their cities well into the future. The Dance-O-Mat being located on a vacant Gloucester Street site for years helped the Council’s designers imagine a permanent dance floor when designing a new civic space on that site. The Lyttelton Petanque Club (see Part I) led, in quite a direct way, to a new town square in Lyttelton, on the same site. But it can go beyond a literal or one-to-one relationship: our Tool Lendery (and other things like it) contribute to the sense that a sharing economy is both desirable and possible to achieve, which gives fuel to the idea of establishing a new community currency or other ideas not directly related, but with shared principles.

We know that projects like the Pallet Pavilion, Dance-O-Mat and Sound Garden led to Christchurch (can you imagine?) being celebrated in Lonely Planet as a must-see global destination in 2013. We know that these shifting perceptions changed the sense of what’s possible in this place, and that much larger projects like the enormous government-led Tākaro a Poi Margaret Mahy Family Playground (that Gap Filler had nothing to do with) wouldn’t have been imagined or attempted here previously. Changing the sense of what’s possible can also change people’s own sense of who they are or who they could be and what roles they could play in society; it can change the collective sense of identity of a place.

The Pallet Pavilion was a temporary venue for all sorts of events at a time when most central city venues were closed for repairs. Over 1.5 years it hosted more than 200 events. (Photo by Maja Moritz.)

Almost a zero-waste building: the pallets that formed the floor and walls, the crates that formed the stools, nearly everything else was borrowed. After 18 months it was deconstructed, and all the pallets, crates and more went back into circulation.

For quite a few years in Christchurch people felt empowered and inspired to act upon their imaginations and bring things to life, to experiment, to do things differently. There were hundreds of small-scale projects by Gap Filler, Greening the Rubble, FESTA (Festival of Transitional Architecture), street artists, Plant Gang guerilla gardeners. There were bigger projects like the Re:Start container mall; Shigeru Ban designed us a cardboard cathedral; food trucks and caravans propagated wildly in a city lacking buildings. People-centred design and activity gathered momentum and put Christchurch on the map. Public lectures by visiting urban designers would attract full houses. There didn’t seem to be a publication around that didn’t feature this creative explosion and interest in the future Christchurch: the Guardian, National Geographic, The New York Times, Monocle, the ABC, the BBC and on and on it went.

This was an incredible burgeoning of civic imagination that Gap Filler both tapped into and helped propagate. The small stuff cultivated much bigger aspirations. These placemaking projects worked as experiential futures, giving a sense – or options – for what the future city could be like. In Part I, I suggested that grassroots urbanism can help shape people’s desires. What many people experienced when they (for instance) discovered the Dance-O-Mat wasn’t ‘a public dance floor’ that led to the possibility and maybe desire for a bigger, better public dance floor. Rather, people experienced something more like ‘a place for spontaneous play and joy with others’. This latter desire could be manifested in all sorts of diverse and creative ways: urban food forests, interactive projections, repair cafes, you name it. Placemaking helped develop a heightened ability for people to collectively reimagine their urban spaces or their roles in the city, to extrapolate, to understand new ways of being in the city, new systems, new realities. A lot of people here were up for some seriously aspirational stuff.

We – worldwide – need hope and ambition more than ever now. We need to use placemaking as a form of prototyping and storytelling about what’s possible: to grow our capacity for imagination so that as a society we can start to believe in positive futures rather than apocalyptic ones.

You can view and comment upon this article on LinkedIn.